Will Rio Tinto stay or will they go (now)

Jason Lindsay

Head of Equities, Octagon Asset Management

First published by NBR on 22 August 2023

ANALYSIS: For the first time Rio/NZAS do not hold all of the negotiating cards.

More than a half-century ago, in November 1971, the then Prime Minister of New Zealand Keith Holyoake flew to Invercargill to open the aluminium smelter at Tiwai Point powered by the newly commissioned Manapouri power station.

The dam project was controversial at the time, sparking outrage from environmentalists, despite the Minister of Works and Electricity, Hugh Watt, describing it as “the most important single step in industrial development taken in New Zealand’s history”.

The smelter is currently 79% owned by Rio Tinto, with the remaining 21% owned by Sumitomo Group. Rio, or its predecessor – Comalco – has a history of reopening supposedly water-tight contracts dating back as far as the 1960s when Comalco backed out of building Manapouri. The New Zealand Government stepped in to build what is widely regarded as one of New Zealand’s great engineering feats. A 700MW (subsequently increased to 850MW but resource consent limited to 800MW) underground power station was constructed with the power station machine hall excavated from solid granite rock 200 metres below the level of Lake Manapouri. A long-term electricity contract was negotiated between the Government and Comalco.

Leaky electricity contracts

After decades of cheap electricity, New Zealand Aluminium Smelters (NZAS) signed an 18-year electricity supply agreement with Meridian Energy in 2007. The agreed price was much closer to the prevailing market price and was due to come into force from April 2013. Before that contract even commenced, NZAS attempted to renegotiate the contract, successfully achieving a lower-than-market price and a one-off government payment of $30 million in 2013.

In 2015, Meridian Energy (along with Contact Energy) renegotiated the price closer towards market for 172MW of the 572MW contract. Subsequently, an electricity supply for pot-line number four (previously closed in 2012) was secured in 2018 taking total contracted volumes to 622MW. The total load was supplied by Meridian Energy with small back-to-back contracts from Contact Energy, Genesis Energy, and Mercury.

After a number of years of uncertainty, with new contracts in place and the fourth pot-line reopened, investors had become comfortable that the smelter was going to remain open in the medium term. Fast forward to October 2019, when NZAS major shareholder Rio Tinto announced its intention to initiate a strategic review of Tiwai Point. The review was to consider all options for the future of the smelter, including the option of closure. Rio cited relatively high energy and transmission costs, difficult trading conditions, and upcoming capital expenditure to keep one of the pot-lines open as reasons for the review.

In July 2020, Rio made the shock announcement that the smelter would close in August 2021 and negotiations with Meridian Energy around a new deal began. In January 2021, Rio announced it would extend the life of NZAS to at least December 31, 2024 (the smaller 50MW pot-line number four was closed in March 2020 due to Covid restrictions and has not reopened) with Meridian Energy and Contact Energy offering a deeply discounted price, believed to be around $35/MWh (excluding transmission costs), to avoid their generation being stranded in the lower South Island.

Why does all this matter?

Apart from being the largest employer in Southland, NZAS uses approximately 13% of New Zealand’s electricity to produce more than 330,000 tonnes of the world’s purest aluminium, most of which is exported offshore.

Whether the smelter stays or goes has a material impact on the wholesale electricity price and the build profile of new renewable generation. In turn, where the wholesale electricity price path tracks has a material impact on the financial performance of the listed generator/retailers (gentailers) being Meridian Energy, Contact Energy, Mercury, Genesis Energy, and Manawa Energy. Combined, these gentailers produce and retail most of New Zealand’s electricity.

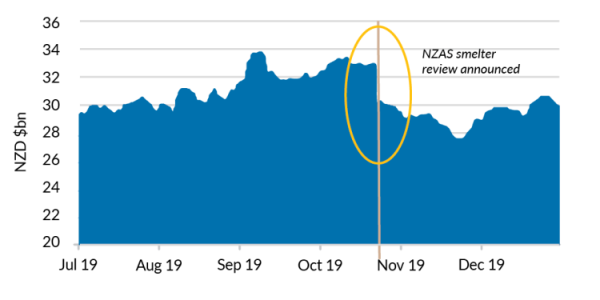

When Rio announced its review on October 23, 2019, investors wiped $2.75 billion off the five listed gentailers combined market capitalisation in one single day, and a further $3b (to make a 17% fall cumulatively) in the month following.

Change of tack

In recent times, Rio has struck a more conciliatory tone, expressing its willingness to sign a new long-term contract. It appears there is virtually no chance of an exit reflected in current share prices. There are a number of perfectly good reasons for this, including;

- Lower South Island transmission (Clutha to Upper Waitaki) has been upgraded allowing potentially stranded generation to flow North;

- Meridian Energy has done a good job diversifying its reliance on the smelter (at one stage smelter load represented almost 50% of its New Zealand generation) and appears to have offered lower volume to further reduce its exposure;

- there are viable alternatives to use the electricity, such as converting coal-fired dairy boilers to electricity, production of hydrogen, and supply to electricity-hungry data centres (albeit the combined is unlikely to fully replace the smelter load);

- Rio Tinto’s recent change of tack globally to committing to low-carbon aluminium production (and to be a better corporate citizen in general);

- the rehabilitation and closure provision has blown out to $671m due to inflation and an assumed early closure. This means if the smelter is cashflow breakeven, Rio is incentivised to run it as long as possible to delay the cash impact of this liability;

- technology advances mean the smelter can shed load for short periods, meaning when hydro lakes are low, the electricity can be diverted elsewhere (demand response); and

- Tiwai Point is now one of only two remaining smelters producing ultra-high-purity aluminium.

Profitability of the smelter

Other than the aluminium price (and alumina input) the largest swing variable to profitability is the price of electricity. Every $10/MWh increase in electricity is a $50m transfer of profit from the smelter to the gentailers.

NZAS produces financial accounts. However, due to the existence of intercompany charges, these are not always the best measure of the profitability of the smelter. Complicating matters further, a large chunk of NZAS aluminium sales attract a premium due to one of the four pot-lines producing ultra-high-purity aluminium. The smelter is also nimble and innovative with the ability to make hundreds of different products (at higher margin).

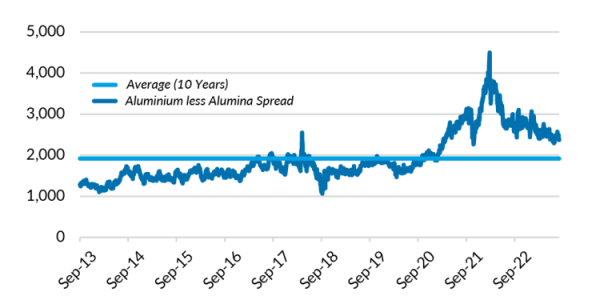

A couple of recent developments are working in the smelter’s financial favour. Transmission pricing has been reviewed, meaning the smelter is paying less (but still some) of the North Island transmission upgrades that it does not use. Second, the aluminium price less alumina price (in NZD) – while off its Covid highs – is well above the price for much of the last decade.

The New Zealand broker analyst community unanimously expects a material increase in the headline price paid for electricity with a common range of $25-$35/MWh noted. This is a significant impost on the smelter. It is likely the smelter is aiming for a number at the lower end of that range as a base electricity price and maybe some linkage to a higher aluminium price (ie, if the smelter wins the gentailers win).

This is less attractive to the gentailers as their earnings become more volatile and exposed to a commodity price they can’t control, but all options are likely being explored. More attractive to the gentailers is demand response from the smelter, where a clear sharing of benefits between the generators and the smelter makes sense. This should result in a lower net electricity price than the headline price increase suggests.

A number of broker analysts attempt to calculate the smelter profitability based on the incomplete information publicly available. As at today’s aluminium price (in NZD), it is likely the smelter could withstand an electricity price more than double the current level and still be cash profitable (after maintenance capex).

Having the smelter operate on very fine margins only incentivises another contract reopening down the track, so all parties will be looking for a sustainable solution. This makes a lower base price, and some linkage to the aluminium price, more likely. Any demand response the smelter can offer will be covered by a separate contract.

Over the past two years, Rio has been on a charm offensive with the Government, media, and financial markets and is making the right noises about wanting to stay. Local management including Chris Blenkiron, the well-respected CEO of NZAS, appear to have played a more prominent role in negotiations (different from previous negotiations that were led from Brisbane).

The 800 direct employees, the Southland economy (it is estimated a further 1600 jobs are indirectly connected with the smelter), the listed gentailers, and their investors are hopeful of a deal pre-Christmas but it has to be one that makes sense.

A higher electricity price, demand response offered, better environmental practices, and a surety in contract (commitment to a longer notice period and provision of collateral so Rio can’t do the same thing in a few years’ time) would all be a step in the right direction from an NZ Inc point of view.

The counterfactual is an electricity market in short term (maybe three to four years) oversupply, likely lowering residential electricity prices. New Zealand would also get closer to the Government’s goal for electricity to be 100% renewably generated. Legacy inflexible gas contracts to thermal generators have largely rolled off, meaning thermal plant could likely be retired quickly.

If the smelter stays, it will continue to play an important role in supporting the Southland economy, and the country, in the form of the export of highly skilled labour and renewable electricity. But only at the right price. A watertight, long-term contract would allow the electricity market to get on and plan for a near 100% renewable electricity generation future without the threat of a major user of electricity departing, leading to an oversupplied market.

The market clearly believes NZAS is set to remain open and the gentailers’ share prices would suffer if no deal is reached. The focus on decarbonisation means the economics of hydro-backed aluminium smelters have never looked better. Tiwai Point still suffers from its lack of scale, age of plant, distance from major markets, and (at a higher assumed electricity price) more expensive electricity but, for the first time, Rio/NZAS do not hold all of the negotiating cards, which should mean a better outcome for the electricity generators supplying NZAS.

Disclaimer: This article has been prepared in good faith based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable and accurate. This article does not contain financial advice. Octagon Asset Management is the investment manager for Octagon Investment Funds and Summer KiwiSaver scheme and some of the portfolios own securities issued by companies mentioned in this article. This article was supplied to NBR and first published 22 August 2023.

This is not a recommendation to buy or sell any financial product and does not take your personal circumstances into account. All opinions reflect Octagon Asset Management judgement on the date of communication and may change without notice. Past performance is not a reliable guide to future performance.

We recommend you take financial advice before making investment decisions. We have prepared this web page in good faith based on information obtained from other sources, but we do not guarantee the accuracy of that information. We do not make any representation or warranty (express or implied) that this web page is accurate, complete, or current and to the maximum extent permitted by law disclaim any liability for loss which may be incurred by any person relying on this web page.